Sližys Raimundas

Since the end of the 1970s, the painter Raimundas Sližys has existed as an exceptional figure in the context of Lithuanian art. Unlike many painters, the object of his brush was the social space of the city – this fascinated and at the same time disturbed art critics, who could no longer apply the popular romanticized interpretations based on the chain of expression of “spirit – nation – village”. Of course, Sližys was neither the first nor the last in the history of Lithuanian art in this regard. However, he was truly special.

The painter was born in 1952, graduated from the Vilnius Academy of Arts in 1976, and has been a member of the Lithuanian Artists’ Union since 1980. His subtle, well-technological (the artist worked as a restorer for a long time) painting was popular: by 1995, Sližys had held 9 personal exhibitions, and his works adorned the expositions of over 60 group exhibitions. Both in Lithuania and abroad. In principle, any prominent artist of Sližis’ generation could boast a similar biography. However, the content hidden in the seemingly conventional form of legitimization of creativity is not so conventional.

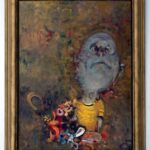

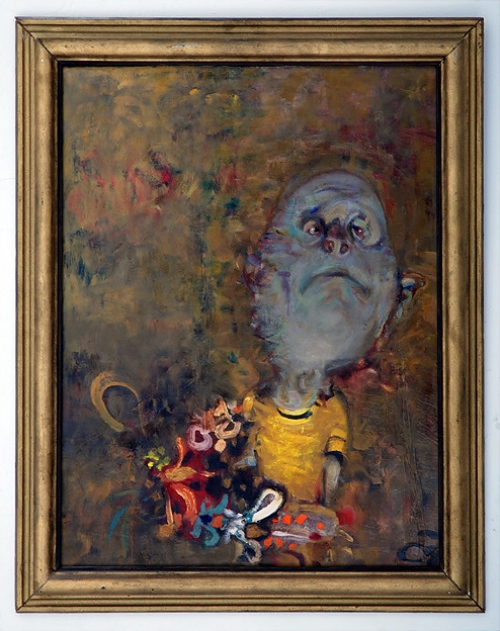

Perfectly sweet harmony of colors, smooth melting of soft forms in a decorative or completely abstract background, details of luxurious Klimtist openwork are scratched and coagulated like fog in paint deposited on the canvas with a sharp varnished nail. Virtuoso but gentle strokes, figures and planes are composed with Japanese sophistication. Such is Sližis’ formal expression.

Many critics praised Sližis for his modernist intransigence with bourgeoisness, for his irony. It is easy to see that this is more a merit of the plot than of the form. Before you, fat bald women puff out, a pointed-heeled shoe flashes, underdeveloped tentacles helplessly gnaw, fluffy curls smolder with orange smoke, you are greeted by “o”-shaped lips or a horse-like smile. Before you, bloated and helpless creatures scurry, as a rule, looking away from the viewer. The painter really caricatures with pleasure. However, it is unlikely that Sližys really takes on the role of a social critic and exploits specific vices. On the contrary, the meaningless parade (let’s call this strangely constrained audience) takes place in a vacuum, where the only force of attraction seems to be the painter’s aestheticizing gaze. You will not receive any ethical/aesthetic reproaches or references, only calligraphically fixed surfaces please the eye.

His charming, ornate canvases fit perfectly into upper-middle-class interiors. This is another feature of Sližis’s painting that makes art critics rack their brains trying to draw a line between art and kitsch. Sližis aestheticizes the very essence of kitsch – passive enjoyment of what is well-known (recognizable), not requiring any intellectual/aesthetic/ethical effort. In this case, value criteria cannot be applied when trying to decipher the transition from kitsch (Sližis’s works themselves as objects of the perceiver) to “good” art (into which kitsch is transformed as the object of Sližis’s work). Thus, the circle closes, and efforts to distinguish kitsch/art no longer make sense.